We tell ourselves a story and we go along believing in it, and then, it turns out, it’s the wrong story, which means we’ve lived the wrong life.

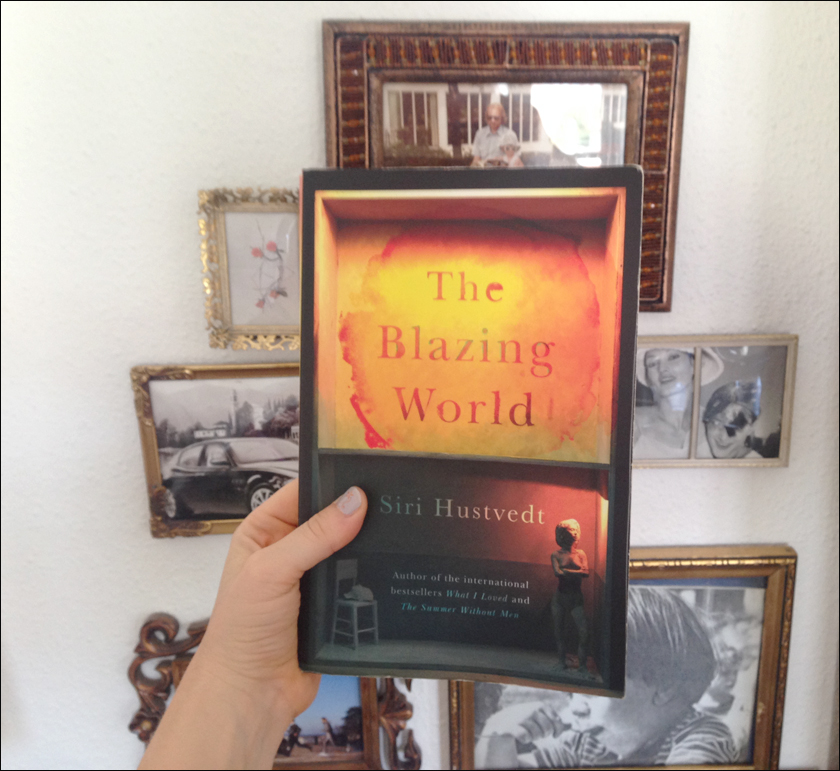

Title: The Blazing World

Author: Siri Hustvedt

First Published: 2014

My Rating: 5 of 5 stars (average rating on Goodreads: 3:60)

I would recommend this book to: Anyone interested in art and/or feminism – or just anyone who wants an amazing reading experience

The Beginning: I started making them about a year after Felix died – totems, fetishes, signs, creatures like him and not so like him, odd bodies of all kinds that frightened the children, even though they were grown up and didn’t live with me anymore.

Artist Harriet Burden has spent her life in the shadow of her famous husband. When he dies, she’s still ignored by the art world. So she decides to experiment and lets three men publish her art. Naturally, I was curious as hell to read what one of my favorite authors would make of this plot.

The truth is Harriet was striking. She had a beautiful, strong, voluptuous body. Men stared at her on the street, but she wasn’t a flirt, and she wasn’t socially graceful or prone to small talk. Harriet was shy and solitary. In company, she was usually quiet, but when she spoke, she was so forceful and intelligent, she frightened people, especially boys her own age. They simply didn’t know what to make of her. Harry sometimes wished she were a boy, and I can say that had she been one, her route would have been easier. Awkward brilliance in a boy is more easily categorized, and it conveys no sexual threat.

I had feared so many traps and clichés, but I should never have doubted Hustvedt. She’s a smart writer and did a brilliant job. The story is told via testimonies of Harriet’s friends and family, and pieces from her own notebooks. I usually don’t enjoy this type of storytelling. I like a clear voice to carry me through the story. But Hustvedt surprised me again with her excellent writing. She managed very elegantly to slightly alter her writing so it fit with the current narrator. My favorite example is perhaps Brune Kleinfeld’s very first statement. This character is an author, and it clearly shows in how Hustvedt suddenly plays around with the language, the way many modern male authors – like her husband Paul Auster – tend to write:

I met Harry during a dog-eared, smudged, scribbled-in-the-margins, stained, and torn chapter of my life.

That made me laugh out loud – such a brilliant cliché! Siri really is superior. And boy, had I missed her! I loved her first and third novel, but didn’t care much for her last two. So The Blazing World was a welcome surprise.

Did I want to live as a man? No. What interested me were perceptions and their mutability, the fact that we mostly see what we expect to see.

I loved Harry/Harriet. I adored her bitterness, applauded her when she lashed out, let her anger and intelligence show – be it through art, words or punches. I loved her passion for art, her strong and fierce nature. She’s one of those characters that don’t disappear when you turn the last page, she demands to stay close to you – even if she has to scream and shout. And I like the way she screams.

It was true they didn’t want Harry the artist. I began to see that up close. She was old news, if she had ever been news at all. She was Felix Lord’s widow. It all worked against her, but then Harry scared them off. She knew too much, had read too much, and she corrected people’s errors.